Two Americas and the lost center

All my life, I’ve been considered very liberal (that means basically “left,” in American usage). But a few years ago my answers on a Pew Center survey of political attitudes placed me firmly in the center of American viewpoints – in fact, in a small, dwindling centrist tail of what Pew’s political typology termed “Solid Liberals”.

I don’t think it’s that I’ve moved rightward: It’s that both right and left in the United States (and, perhaps, worldwide) have moved further and further from that center. In fact, the current version of the Pew typology shows the bulk of the American public – however it appears to the rest of the world – shifting significantly leftward.

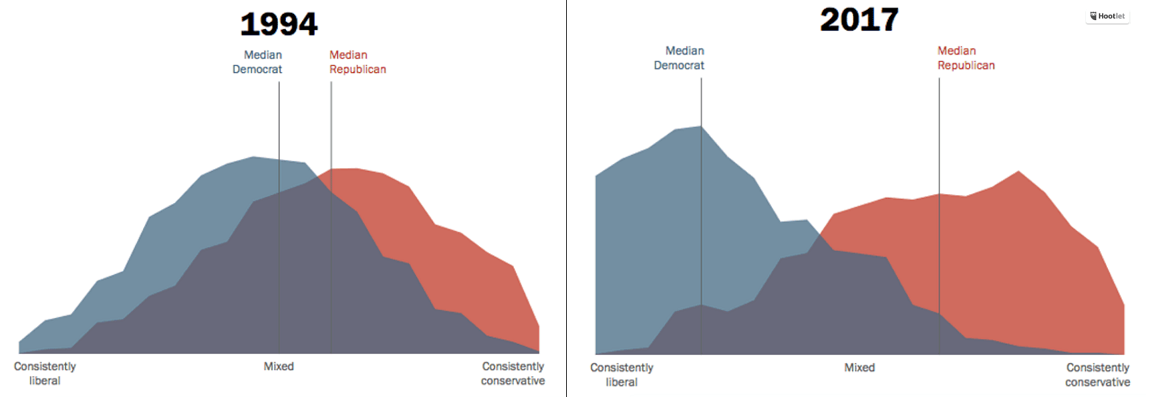

More importantly, though, as a majority of Americans has shifted somewhat leftward, the rest have been shifting, as well – significantly rightward. Comparing the Pew analysis over time shows these two large masses, each distinct, moving past each other like ships in the night:

(This can be seen even more strikingly in the time-sequence animation here.)

Politics are no longer really arrayed along a line presenting something of a traditional bell curve, at the center of which lies the vast bulk of the population, forming, well, a “center.” Instead, whatever lines there may be lie on two separate planes that simply don’t intersect. The challenge today is not that, in William Butler Yeats’ famous formulation, “the center cannot hold”: It’s that there is no center anymore.

In America, and around the globe, today there are two distinct worlds – each, like its own Flatland, never intersecting with, or even able to imagine, the other.

One essentially is embracing an economy rooted in digital technologies. The other is deeply troubled by the economic and attendant social changes being wrought by these technologies.

A debate is now raging in the US – largely on the left – over the main source of the animus that the “traditional” world harbors against its new-technology competitor. This debate over root-cause is reflected in the parallel debate over proper response, which is ripping apart the Democratic Party. Some see the anger and rejectionism of those who support President Donald Trump (or Brexiteers or Marine LaPen or Viktor Orban or the League) as rooted in racism and therefore requiring an unqualified repudiation by self-certified progressives. Others see the problem as driven by underlying economic shifts and therefore amenable to – or at least deserving exploration of – palliative policies that might heal the nation’s divide (and improve progressive electoral prospects). I side largely with the latter in this debate, both because it provides the deeper explanation, and because dismissing the other side as – to coin a phrase – “deplorables” is simultaneously too smugly self-congratulatory andultimately hopeless of a resolution.

In truth, the two explanations are intertwined: “Othering” is endemic to human conduct, and racism (as well as denial that it’s racist at all) is peculiarly central to America’s history, economy and social structure – but it should be clear that the increase in open racial and ethnic hostility, and demands for aggressively more active racist and anti-immigrant national policy, is driven by the increased economic anxiety of those in Trump’s base. The signature – if not sole significant – legislation the current administration and Congress have produced is the December 2017 tax bill that, as I wrote here, essentially amounts to a declaration of economic, not culture, war on the socially liberal, “New Economy” states of the two coasts: Only indirectly attacking these liberal regions’ “values” – such as by promoting fossil fuels over renewables and taxing college endowments, student loans and graduate incomes – it was, rather, primarily an assault on the “New Economy”, and an income transfer to the “Extractive Economy”.

The fact is that the economic changes and social shifts against which the reactionaries are reacting are inseparable, because one drives the other. The effect of technology on traditional cultures can best be appreciated by stepping, for a moment, outside the current Western context and looking at different cultures and different times. For instance, the international strategist George Friedman, in his book The Next One Hundred Years, argued a decade ago that America’s threat from radical Islam would decline because Islamic societies themselves would be plagued by divisive culture wars, in part driven by modern technologies. Which technology in particular did Friedman have in mind? Birth control.

Birth control technology dramatically changes the economics of being a woman, and thereby gender and family relationships. This may be the largest, and longest-lasting, social change in the US to come out of the turbulent 1960s; Friedman sees its impact on the even-more-traditionalist cultures of the Middle East as even more explosive – and the backlash even stronger.

Going further back, the technological innovations of the industrial era generated revolutions – and reactions – in not just politics but also in the nature of family and private life, where people lived and what communities might thrive or decay, and the rituals, both religious and of daily life, by which people had come to define themselves for eons. Though we tend to overlook it because it was so long ago, the advent of agriculture did the same. But these prior technological revolutions generally affected lives and communities over a timescale of generations, even millennia – not a contemporary business cycle. And therein lies the great challenge of the current moment: Technological, economic and social change today proceeds at a pace that looks less like a slow phase-change – like, say, the melting of ice, where for a long time liquid and solid water coexist in the same space – and more like a sudden rupture: the “critical states” of chaos theory.

Compounding that, of course, all these different, almost-entirely binary choices are almost-entirely correlated. There certainly must be some religious-fundamentalist Republicans who hunt and raise their own food in New York City, and liberal, transsexual, immigrant tech entrepreneurs in the prairie states. But probably not many. The US has almost thoroughly sorted itself politically over the last few decades – the number of “swing counties” has declined markedly, and “swing states” have nearly vanished – but this political sorting is merely a byproduct of the cultural and economic: Americans increasingly want to live around those with whom they feel culturally comfortable; and people interested in the tech industry just aren’t flocking to western Kansas, while those interested in working in extractive industries won’t find much work in San Francisco.

American politics grew polarized over the last generation because the nation’s economic success rendered economic differences less salient than social issues – like abortion, race, sexuality, and culture – that are less susceptible of compromise. But now, the economy one lives within has become an almost-entirely binary – and cultural – choice, too.

The result is increasingly (although we may have reached “terminal velocity”) two entirely distinct Americas. Yes, these are largely physically separate: a so-called “red” (i.e., Republican and conservative) interior – except for whatever urban islands, from large cities like Denver and Atlanta to smaller, quirkier ones like Bozeman, Montana – ringed by “blue” coastlines. But more importantly they are economically, demographically, religiously, and in every other way significantly different. They don’t even like the same kinds of TV shows, or laugh at the same jokes; their sources of information overlap almost not at all. And they certainly place very divergent levels of faith in institutions of all sorts – and, especially, in democracy. These are essentially closed, separate and, in their own manner, largely homogenous universes.

With that near-complete separation has come a growing sense of incompatibility: These two nations, these two non-intersecting planes, don’t only choose not to live together – they believe they can’t.

Each, of course, blames the other, with little recognition of its own complicity in the spiraling hostility: The authoritarian, fundamentalist, ethno-nationalist, and profoundly anti-science leanings of large swaths of Red America justify to Blue America its conviction that it can’t possibly live under the other. As a result, conservatives increasingly ridicule liberal states for apparently wanting to secede from the Union (a prospect, as I’ve written here and elsewhere, that I consider likely in the longer term); Alex Jones, a prominent conservative radio host and conspiracy theorist, even warned his credulous listeners that liberals were staging an armed coup of the federal government over the recent Independence Day holiday.

But few of those in the Trump ascendancy bother to recall the mounting calls for secession by their own Red States under former President Barack Obama or their threats of armed insurrection if Trump were denied the presidency. Those feelings were neither more nor less reasonable than those of liberals who now see their values and lives as inherently threatened by rising right-wing authoritarianism: The global economy that has made liberal regions far wealthier has torn like a wrecking ball through the communities of the interior – with little apparent concern from the elite – while liberalism, suddenly cultural ascendant, has become increasingly illiberal in its unwillingness to tolerate what it views as intolerance.

One of these two nations clearly was winning the economic, cultural and political wars until recently; the other has predictably struck back with a vengeance. Both now believe, probably correctly, that they are in an existential struggle with the other where only one will survive.

There are, in short, two sides – but no center.